Conveo Super Bowl Ad Impact Study 2026

Forget post-game polls. Forget the morning-after rankings. This report is built on something different: what 147 viewers actually felt, said, and did while watching Super Bowl ads in real time and in post-game interviews.

Rhys Hillan

Research & Customer Impact Lead

Articles

Qualitative insights at the speed of your business

Conveo automates video interviews to speed up decision-making.

What viewers really felt about Super Bowl ads

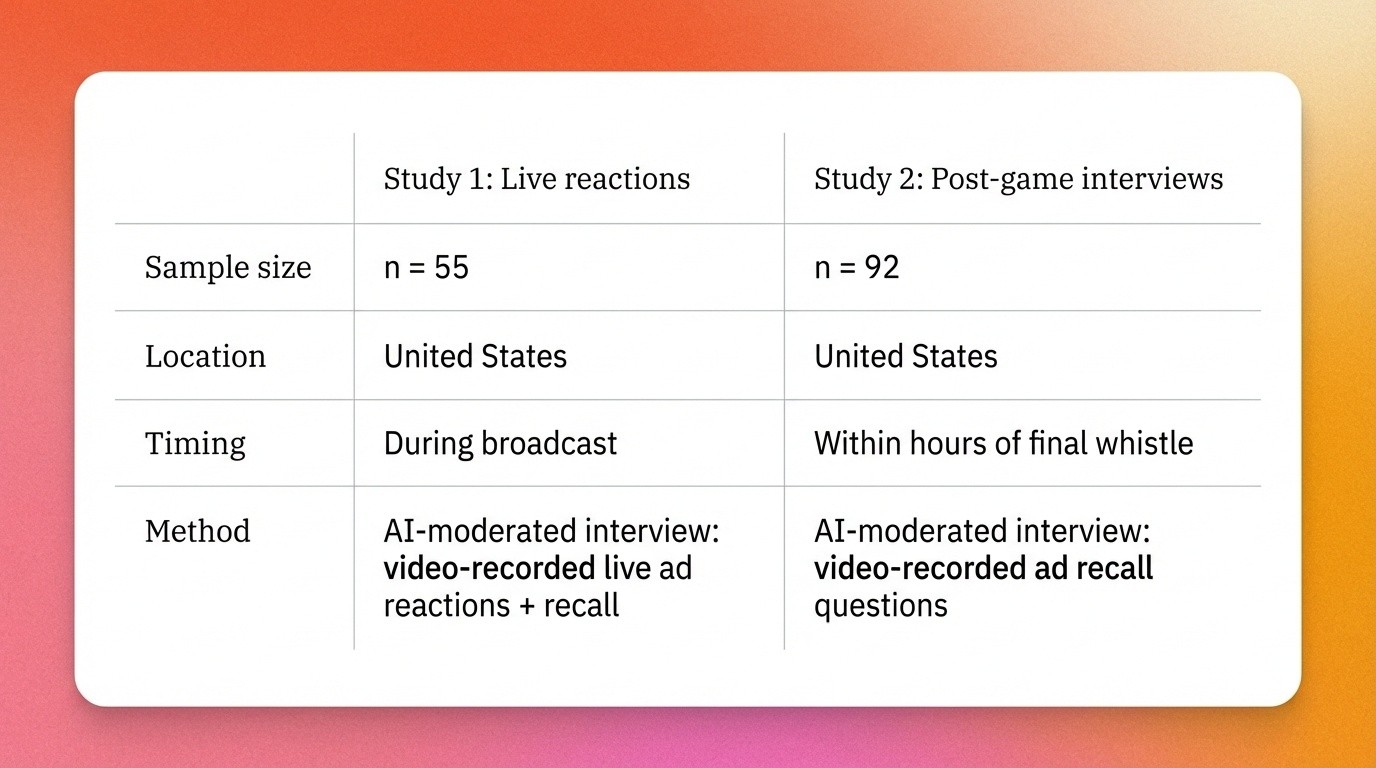

Two complementary studies | n = 147 combined | United States

Executive summary

Forget post-game polls. Forget the morning-after rankings. This report is built on something different: what 147 viewers actually felt, said, and did while watching Super Bowl ads in real time and in post-game interviews.

The combined story across live reactions and post-game recall is consistent:

The Super Bowl functions as an "ad event." Viewers describe the broadcast as appointment viewing where ads are a central reason to tune in, even for non-fans.

Humor + warmth + nostalgia + celebrity are the dominant attention engines. These reliably create live reactions (smiles, laughter, sing alongs) and remain the strongest recall drivers in post-game interviews.

The biggest risk isn't dislike, it's confusion and weak brand linkage. Viewers often remember the moment (scene, joke, celebrity) but not the advertiser, and sometimes misattribute the brand entirely.

Celebrity is an accelerant, not a substitute. It can increase attention, but also crowd out brand meaning and trigger "overused" or "out of place" complaints.

What follows is the full picture: eight themes drawn from the data, with tables and video clips that let the evidence speak for itself.

————————————————————————————————————————

PART 1: ABOUT THE RESEARCH

What sets this research apart?

Most Super Bowl ad research tells you what people say they thought. This research captures what they actually felt, in the moment, in context.

The problem in how Super Bowl ads are traditionally measured

The industry's go-to tools for evaluating Super Bowl advertising share a common flaw: they strip away the context that makes the Super Bowl the Super Bowl.

Ad Meter-style panels ask thousands of people to rate ads on a scale, usually the next day or later. By then, social media has already shaped opinion. The viral tweet about the Instacart ad, the meme about DraftKings, the group chat consensus: all of these overwrite what the viewer originally felt. What you're measuring isn't the ad's impact. It's the internet's verdict, reflected back through the viewer.

Pre/post recall surveys measure what sticks in memory after the fog of 50+ ads, a halftime show, and (for some) several beers. They're useful for brand tracking, but they can't tell you why something stuck or when a viewer checked out. A high recall score and a high confusion score can coexist, and often do.

Social listening and sentiment analysis captures volume and valence, but not depth. A tweet saying "that Uber Eats ad was hilarious" tells you something. A viewer walking you through why the Matthew McConaughey bit worked, what reminded them of their childhood, and the exact moment they realized it was an Uber Eats ad is far more insightful.

Lab-based ad testing removes the single most important variable: the living room. Super Bowl ads don't air in isolation - they happen in real-life context. They compete with nachos, bathroom breaks, halftime arguments, and a room full of people who all have opinions. An ad that tests beautifully in a quiet research facility may die on the couch.

The Conveo Approach: What we did differently

We went into the living room. We interviewed viewers in their homes and normal environments, in the moment of truth, and immediately after.

Study 1 (n = 55): Live, in-the-moment reactions. Viewers recorded video reactions during the broadcast, as ads aired, in their actual viewing environments: couches, parties, living rooms with the volume up and the chips out. No controlled setting. No isolated ad playback. The full, messy, competitive context of a real Super Bowl viewing session.

Afterward, participants completed forced-tradeoff questions: pick one favorite, one funniest, one most confusing, one worst. No "rate all ads 1-5" hedging. When you force a single choice, you learn what people actually prioritize, not what they're willing to give a polite score to.

Study 2 (n = 92): Post-game depth interviews. Within hours of the final whistle, 92 participants sat for structured interviews, walking through what they remembered, what they loved, what confused them, whether they could connect the story to the brand, and what they'd talk about the next day.

This isn't recall data collected three days after the internet has done its work and Super Bowl conversations have been the hot topic in every social setting. It's recall captured while the memory is still warm, before the takes harden, before the "I always thought that ad was good" revisionism sets in.

Why two studies, not one?

Each study catches something the other misses.

Live reactions capture the immediate instinct: the laugh, the cringe, the "wait, what?" They're unfiltered and unedited, recorded before the viewer has had time to construct a narrative about what they think.

Post-game interviews capture the stickiness: what actually stuck, what the viewer can reconstruct, and, critically, whether they can connect the experience to a brand. The gap between "I loved that ad" and "I have no idea who it was for" only shows up when you ask people to think back.

Together, they create a before-during-and-after: what the ad did to the viewer in the moment, and what the viewer kept an hour later.

What this methodology makes possible?

This paired methodology surfaces insights that no single approach can:

The entertainment-brand gap, quantified. By comparing live emotional response with post-game brand recall, we identify exactly which ads entertained without branding (the "that was hilarious... who was it for?" problem) and which ads branded without entertaining (the "oh, it was a pharma ad" shrug).

Confusion caught in real time. Traditional research spots confusion after the fact. Live reactions catch the exact moment a viewer's face goes from engaged to lost. See when the narrative breaks, not just that it broke.

The social layer. Interviewing audience in their real environment meant we captured the group dynamic: the ad that made the whole room laugh, the one that triggered a debate, the one that made everyone reach for their phones. These are variables lab research can't replicate and surveys can't measure.

Forced tradeoffs reveal real preference hierarchies. Being asked to pick one best and one worst, means you're not being generous. You're being honest. The fragmentation pattern in "best" (no consensus) versus the clarity in "worst" (DraftKings, by a mile) is a finding that only emerges from forced-choice design.

Here's a quick highlight reel of live ad reactions - with plenty more to come.

What were the samples?

Without further ado, let's dive into the findings…

————————————————————————————————————————

PART 2: KEY FINDINGS

The Super Bowl is the Ad Show (and this year proved it)

Participants consistently framed the Super Bowl as appointment viewing, not just for football, but for the ads as entertainment. In many conversations, the game itself was almost secondary. Viewers described setting up snacks, settling in on the couch, and waiting for the commercial breaks with genuine anticipation.

In the coded motivations below, the largest segment watched primarily for ads. But the number alone understates the finding. What's distinctive is the language people use: many describe Super Bowl ads as a shared cultural moment, a yearly ritual, and a "common reference point" people can assume others have seen.

That context explains why certain creative shortcuts work so reliably: celebrities, nostalgia, recognizable music. They're instant handles for group conversation.

Even "ad people" aren't watching in a vacuum; ads are competing with a real-time, living-room context where anything that doesn't immediately register risks being lost to the next chip dip or bathroom break.

"I like how creative they are. I like that there are sometimes like cultural moments that happen when these ads come out that they're sort of something that everyone's experiencing. And it's kind of nice to have a shared experience like that." - FEMALE, US

Humor, Emotion, Celebrity, Nostalgia: The key ingredients that made ads 'pop'

Across both lenses (live + post-game), the same drivers repeat. Viewers reward Super Bowl advertising when it creates an immediate felt reaction: laughter, warmth, surprise, nostalgia, or a moment worth pointing out to someone else.

This isn't a new finding in isolation. But what's striking is the consistency: whether you ask viewers to show you their reactions in real time or walk through them two hours later, the same ingredients keep surfacing.

The implication: these aren't just "nice to have" qualities. They're table stakes for the Super Bowl environment. The ads that break through aren't doing just one of these things well, they're doing three or four simultaneously.

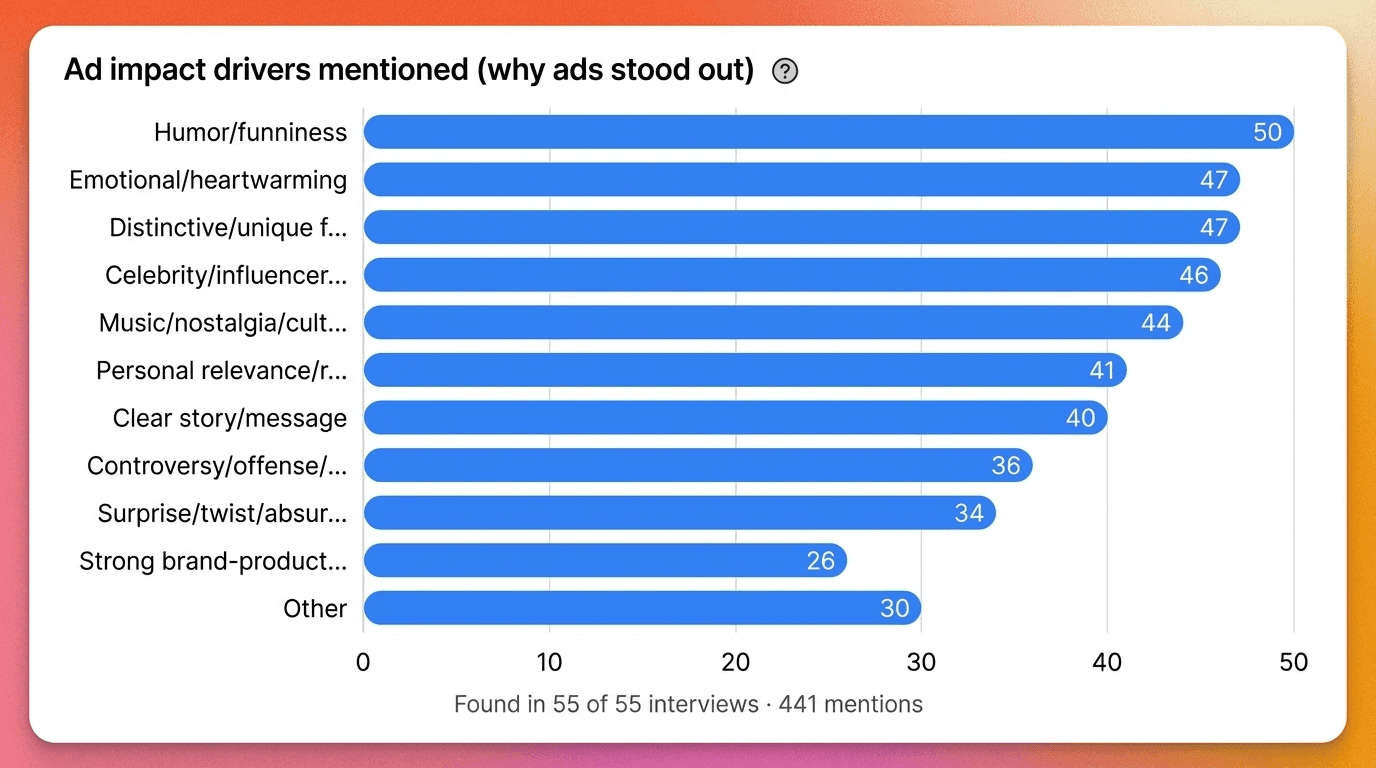

Live-reaction lens: what drove impact? (not always positively)

Humor was a key driver of ad impact, mentioned the most, by almost all participants.

Emotional storytelling and distinctive creative formats tied for second, each mentioned by roughly 9 in 10 participants.

Celebrity presence and nostalgia/cultural references followed closely, with personal relevance and clear storytelling each cited by roughly 3 in 4 participants.

Surprise and absurdity rounded out the list, mentioned by roughly 6 in 10.

Chart from Conveo Super Bowl Ad Impact Study 2026

Post-game lens: themes viewers enjoyed

Ads should entertain, not explain.

In post-game reflection, participants still described the "winners" in terms of tone and creative experience, not in terms of product features. Nobody said "I loved that ad because it clearly explained the pricing model." They said they loved it for reasons like it making them laugh, or jogging a memory, or getting caught off guard by a celebrity.

That's the reality of the Super Bowl ad environment: you're being judged as entertainment, whether you like it or not.

Key Takeaway: Super Bowl ads are entertainment first. Branding works best when it's woven into that entertainment so the "bit" and the brand are remembered together, rather than the story eclipsing the advertiser.

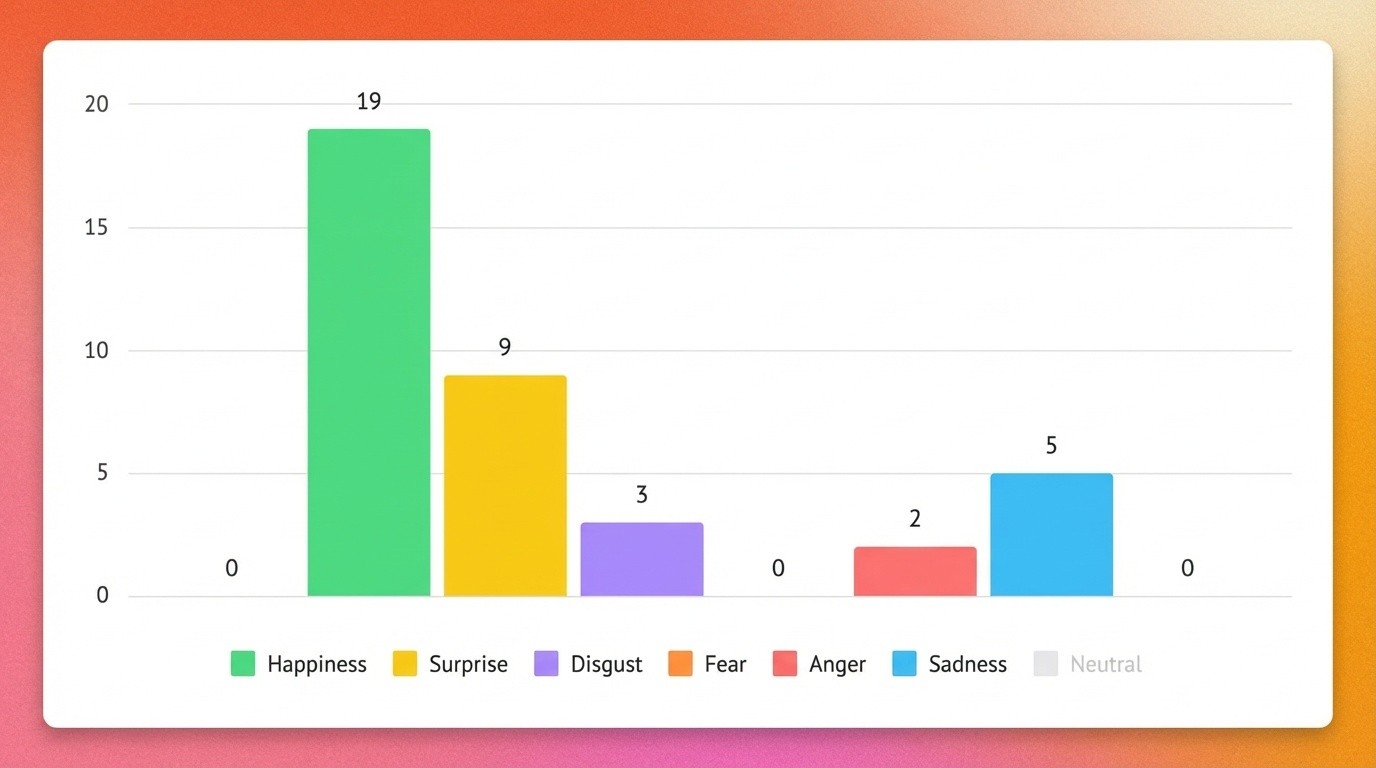

Emotional reactions: Proof the ads were working

Participants reported visible, in-the-moment reactions, especially laughter and smiling. Over a quarter of the sample laughed out loud during at least one ad, and nearly as many reported smiling.

A smaller but important group described tearful reactions to the more emotional spots. We captured many of these genuine reactions on camera with our pioneering multi-modal video interview analysis.

Conveo emotional analysis chart from Super Bowl Ad Impact Study 2026

"The Rocket one definitely had me tearing up so much that I looked it up on my phone to rewatch it again. And then the Good Will Dunkin had me definitely laughing out loud because it was just really funny." — FEMALE, US

"I'm not gonna lie. I sung along and I kind of chuckled or smirked at myself... Like I'm smiling right now just thinking about it." — MALE, US

"I did smile, and I immediately started singing along. I Want It That Way. I have no voice right now because I'm sick. But, yes, it immediately made me sing it, and I paid attention to the whole video." — FEMALE, US

"On these two particular commercials, I was, like, caught up in the moment... I was definitely not expecting him to do that backflip and, excuse my language, bust his ass in such a funny way." — MALE, US

————————————————————————————————————————

PART 3: THEMES DETECTED

Theme 1: Comedy still wins — when it's a moment, not a gimmick

Humor is still the most reliable "breaker" in the Super Bowl environment: it creates an immediate response (smile/laugh), it's easy to retell, and it travels well in group settings.

If you want your ad to be the one people bring up at work on Monday, comedy is still the most efficient path.

But participants also describe a high bar for Super Bowl humor.

A joke doesn't just need to be "pleasant", it needs to feel like a hook. When the humor lands, viewers often describe it as the first time that they actually laughed, or as something they'd bring up later.

When humour was present it often worked equally as a recognition engine: nostalgia, cameos, and "I know that person" moments did a lot of the heavy lifting.

Finally, a small but notable group simply weren't buying it: roughly 1 in 10 live-reaction participants selected "No ad found funny" when asked to pick the funniest.

"Think my favorite ad was a Instacart ad that just looked super chaotic and ridiculous. The whole thing was falling apart from the beginning... But it just it definitely hit. It was funny. Huge production value too, like, the Super Bowl ads used to be." — MALE, US

"Honestly, the whole thing was just discombobulated. It didn't make any sense from beginning to end. I'm seeing Ben Stiller in this kind of pseudo rock concert and they're smashing things, falling over things. You have these dancing bananas up there and the dancing bananas were supposed to connect to produce you would order?" — MALE, US

Theme 2: Emotion that felt earned was often mapped to family

Emotional storytelling was consistently described as "working" when viewers could map the story onto their own relationships or values. In this pod, the most resonant emotional narratives were family-coded: parents/children, growing up, caregiving, retirement, legacy, and "one more time."

A key dynamic is contrast. In a night full of fast, noisy, celebrity-heavy, or tech-forward ads, a calmer narrative can feel like a reset — a short story you can actually follow, with emotional cues that don't require decoding.

Several participants described the emotional ads as the ones that "stood out because they slowed down." That's a powerful insight for creative teams: sometimes the boldest move in a Super Bowl pod is not being loud.

"I liked the Lays ad because with the father and the daughter, and it reflected back when he was, they were both younger. And then currently, he was passing the farm on to him in his retirement. It just seemed like it was more it wasn't crazy like the other ones. It wasn't too, like, science fiction or it wasn't too, like, too dumb. It was realistic. It had a story to it in a short amount of time... calmer, had a story, had some emotion." — MALE, US

Emotional storytelling is a fit question. When the emotional narrative aligns with the brand's existing mental model, it deepens connection. When it doesn't, it can create dissonance strong enough to damage brand perception.

Key Takeaway: The lesson isn't "don't do emotion", it's "make sure the emotion belongs to your brand."

Theme 3: The recall gap — stories outshine brands

This is arguably the most important isight for brands spending millions of dollars on a Super Bowl spot.

Almost 3x the number of people recalled entertainment over recalling brand.

Viewers frequently recalled the creative first - the moment, joke, celebrity, or story beat - and only secondarily the brand. In other words: the ad was working as entertainment, but not necessarily as advertising.

Brand linkage clarity

The brand linkage data paints a more nuanced picture. These categories are not mutually exclusive: a single viewer can experience clear linkage for some ads and weak linkage for others within the same session.

Two-thirds of people who clearly recalled both ad and brand also include people who, for other ads, couldn't name the advertiser.

Remembering an ad does not mean brands are recalled 1 on 1:

Only 1/3 of participants recalled both the ad and the brand

In 1 out of 4 ads, people recall the ad or story but do not tie a brand to it

In less than 1 out of 4 instances, people know the brand but are unclear about the story tied to it

What links an ad to its brand?

When viewers did connect story to brand, they most often credited celebrity, on-screen logo/branding, or the product being shown prominently. But the second-largest group — 21.1% — couldn't name any cue at all.

This underscores how fragile brand linkage is, even for viewers who remember the ad vividly.

This next clip is a clean illustration of the problem. He can replay the ad in vivid detail but the brand handshake is fragile.

This isn’t a reflection of bad performance of the ad overall (it performed very well!) but illustrates how ad recall can be unreliable.

"Another one that I remember was, I believe it was Uber Eats. I believe it was. But it was just hilarious. It was the one with Ben Stiller. It started off kinda like I was wondering what was going on, but they were showing, like, these big bananas..." — MALE, US

Key Takeaway: For Super Bowl creative, the question isn't "was it entertaining?" It's "did the entertainment carry the brand with it?" The data says: often, no.

Theme 4: Confusion is the achilles heel

Super Bowl ads can be entertaining and still fail if viewers have to ask basic questions: 'What is this for?', 'What am I supposed to do?' 'Why is this brand involved?'

Importantly, participants didn't describe confusion as a minor annoyance.

Confusion often came with impatience ("I'm not doing the work to figure this out") and sometimes with resentment ("you spent all this money and didn't communicate anything").

In the coded drivers, the most common confusion sources weren't "too weird" — they were structural: brand not connected to the content, unclear product or offering, and narrative complexity that prevented a clean takeaway.

When people said an ad "fell flat," the top reasons map directly back to confusion. Viewers either didn't understand it, or didn't feel it earned their attention. The pattern is consistent across both studies, which makes it hard to dismiss as coincidental.

Key Takeaway: The #1 creative risk isn't being disliked. It's being unconverted into meaning. If viewers can't translate the entertainment into a clear brand + offer, the ad becomes a memorable short film with a missing sponsor. And at $7 million for 30 seconds, that's an expensive short film.

Theme 5: The celebrity paradox - accelerant or sabotage?

Celebrity use is omnipresent in Super Bowl advertising, and viewers definitely notice it. But "celebrity" functions in two competing ways, and the data surfaces both clearly.

First - the hook: you look up from your phone, you point at the TV, you play the recognition game ("is that Tom Brady?"). Several participants described this as a kind of sport-within-a-sport, tracking cameos and trying to identify everyone.

It's engaging, it's fun, and it keeps eyes on the screen.

Second - the distraction: the celebrity becomes the memory while the brand becomes a blur, especially if the brand is only revealed at the end. The net result is an ad that people can describe in vivid detail ("the one with Jennifer Aniston") without being able to name the advertiser.

Celebrity-brand fit is polarized

When asked about celebrity-brand fit, the results are strikingly polarized. "Completely out of place" outscores "perfectly matched" by a factor of six. This suggests that the default viewer reaction to celebrity casting is skepticism, not excitement.

Celebrities earn their keep when the fit feels intentional. When it doesn't, they become the most expensive distraction in advertising.

To understand how to incorporate celebrity successfully, it helps to know why it fails.

Why celebrity backfires

The reasons celebrity fails breaks down into predictable categories.

The most common: the casting feels random and disconnected from the product or message.

The second: the celebrity overshadows the brand entirely.

"I think it happened a lot for me because I was just kind of being like, oh I know who that person is, but then someone new will come on. I'm like, oh I also know who that is. It was keeping me very engaged with the ad because I was very interested to see who else was going to come on the screen. And when I saw Tom Brady I started laughing because big football guy, commentator, why is he in a Dunkin' Ad?" — MALE, US

Key Takeaway: Celebrity works best when it accelerates a brand idea, where they fit the ad theme, product, or brand identity well. It fails when it reads as casting-for-casting's-sake, leaving the viewer with a vivid memory of the person but no memory of the product.

Theme 6: Consumer activation — what ads people talk about (and when)

A key reason Super Bowl ads matter to marketers is that they can become social and conversation currency. People talk about them in real time and in the days afterward, often sorting them into informal categories: "best," "dumb," "head-scratchers," and "ones you have to show someone."

That post-game conversation is where the ad's impact either compounds or evaporates.

The data shows that most viewers do expect to discuss at least on average 3 ads after the game. But there's an important nuance: when people talk about ads, they don't always mention the brand. The conversation often centers on the moment ("the one where the guy falls off the balcony") rather than the advertiser, unless the brand is tightly integrated into the memorable element.

"I'm not gonna post about anything on social media. It's not something I do. But talking about friends. Yeah. Probably all of it. Friends, coworkers. We're definitely gonna talk about it and then share the ones we like the most, share the ones we thought were dumb, share the interesting ones, and then the downright head scratchers." — MALE, US

Key Interpretation: Even when brands "win" by being talked about, the content of conversation may center on humor, celebrity, and moments rather than product — unless the brand is tightly integrated into the story. Being "the one everyone talks about" only matters if they know who you are.

————————————————————————————————————————

PART 4: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BRANDS

What all of this means for Super Bowl creative

Across both studies, a clear hierarchy emerges for brands trying to "win" the Super Bowl ad conversation. These aren't theoretical recommendations — every point below is grounded in what 147 viewers actually said, felt, and remembered.

Earn attention quickly, then keep it. Humor, warmth, nostalgia, and recognition hooks win the first seconds. In a living room full of snacks, phones, and other people, you have about three seconds before someone talks over you.

Make the point legible. Confusion (brand linkage + unclear product) is a primary failure mode. If the viewer has to work to figure out who you are or what you're selling, they won't.

Connect entertainment to brand early and clearly. If the brand appears only as a final-second reveal, you may win a laugh but lose the marketer's objective. The best ads weave the brand into the entertainment so they're inseparable.

Use celebrity as an accelerant, not a substitute. Fit and role clarity matter. When celebrity casting feels random, it doesn't just fail to help — it actively damages brand linkage by becoming the only thing viewers remember.

Design for the context. Super Bowl viewing is social and snack-driven. Ads must survive side conversations and split attentions. The ones that do well are built on immediately recognizable hooks and entertainment, not slow builds or heavy explanations.

Closing comment: The Super Bowl remains the single highest-stakes creative moment in advertising. The brands that win aren't necessarily the ones that spend the most or cast the biggest names. They're the ones that understand the room: loud, social, distracted, and hungry for something worth talking about.

(Disclaimer: All participants in this study have agreed to this content being distributed externally by Conveo for marketing purposes)

Related articles.

Decisions powered by talking to real people.

Automate interviews, scale insights, and lead your organization into the next era of research.